Gay Theater Veteran Looks at Sex on Celebration Theatre’s Boards

When Mart Crowley’s landmark play, “The Boys In The Band” played Off Broadway in 1969, half of the cast members were considered “mentally ill or sick” because of their offstage lives, complicated by their onstage lives in which they played characters who were labeled with a “mental disorder.” These guys may have been the toast of the town but the lemons they were served on the side had not yet turned into lemonade.

Many of these actors were stringently closeted, wearing the mandatory wedding ring, others were less strict, wearing a tell-tale t-shirt now and then; but there was a sense of uneasiness that permeated the proceedings. Not all of the producers were queer; not everyone in the cast was queer; not everyone shared the same degree of homo acceptance.

However, after nearly a century, the official reversal by the American Psychiatric Association that homosexuality was no longer as “psychiatric disorder” in 1973 resulted in a wellspring of gay plays — loosely defined as plays with gay characters and gay themes, written by gay playwrights and performed by gay actors of both genders — flourishing on the New York stages of Ellen Stewart’s La Mama and Joe Chino’s Café Chino, presenting works of Tom Eyen, Victor Bumbalo, Robert Patrick, and Doric Wilson (among others).

This marked the first time in the American theater in which gay artists who created onstage worlds of gay stories that would entice, illuminate and intrigue audiences could not potentially be criminalized, literally, for merely leading their offstage lives. And onstage gay characters could behave as batshit crazy as their heterosexual counterparts and not be thrown in the hoosegow.

The West Coast soon found its gay footprint at Smitty’s Coffeeshop, a teensy venue in East Hollywood where the proprietor sold exotic coffee drinks, which served as your ticket to see the show. Robert Patrick’s T-Shirts made history with a Los Angeles Times review that attracted a lineup of celebs: Elizabeth Montgomery, Robert Foxworth, Richard Deacon, Charles Pierce, and George Chakaris among them.

Imagine the newfound freedom of rehearsing with a team of gay men, unmasked, diving into the material full-on after years of self-censorship, denial, often gauging every word and gesture in fear of being caught because you were gay, playing a gay role, in a gay play. Liberation wasn’t only taking place on the streets, honey, we were inhabiting rehearsal halls across America: strutting, prancing, swaggering with all our might.

The bonding that went on during the preparation of these plays had an added level of intensity and intimacy that was surely based on the level of openness many of us shared. And let’s be honest: we were in the nascent stage of our theatrical voyages. Did we engage in verbal innuendo during the rehearsal process? Touchy-feely? Overt flirting? Think about it. The initial themes of the theater pieces that launched us into the stratosphere of a larger artistic forum often riveted on the trials and tribulations of coming out of the closet, enunciating our quest to avoid being marginalized as nut cases. We had been suppressing feelings of sexuality that had been defining us as bad, immoral, and mentally ill for decades; it was about time we reclaimed our sexuality. And if the plays we presented didn’t capture that stance specifically, the subtext was likely to be played out among cast members, the staff, the crew, and maybe some anonymous audience member and an actor in the cast.

It’s not called “Castigation Theatre.” Celebration!

I believe that the ribald rehearsals and backstage improprieties that initially took place were a natural release of the freedom gay men felt in their bodies, the bodies that were vessels they also employed to express emotionality.

Unaccustomed to feeling such unbridled joy, it must have been difficult to switch gears, especially when the scripts were often in alignment with their internal and external selves — their identities, if you will.

However, we have matured as a community. Or have we? Are we stuck? AIDS in our theater spaces certainly elevated our artistic sensibilities. Generally speaking, offstage we were profoundly supportive of those in our midst who were HIV-positive; we raised money and consciousness. I doubt there was much dilly-dallying in the wings during AIDS plays, but I do know of one profound love affair that soared.

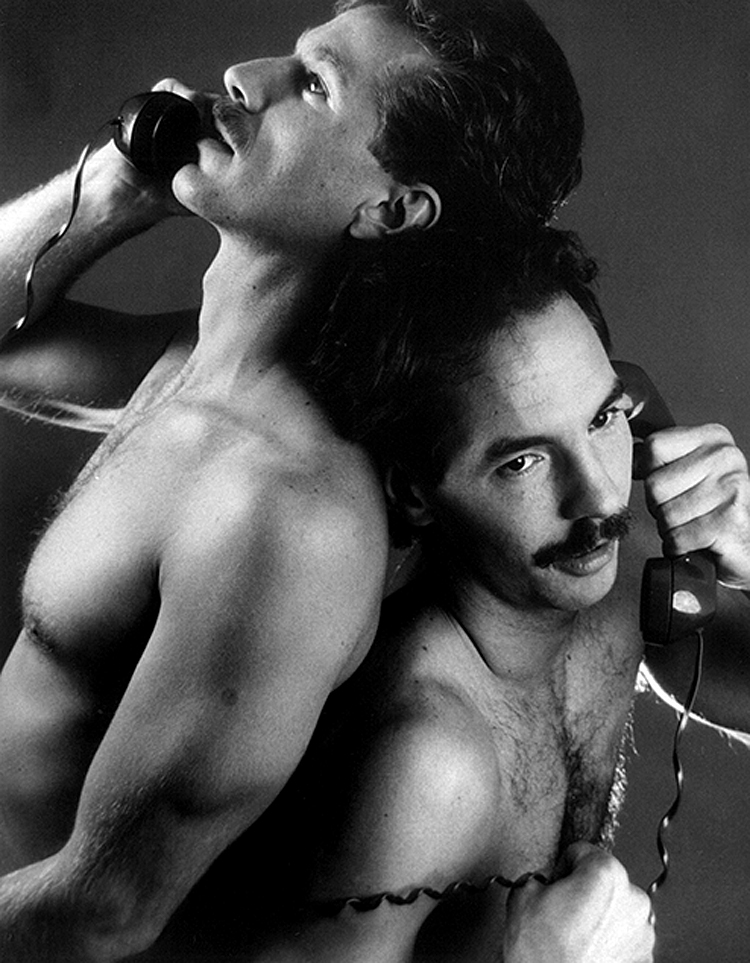

Joe Fraser and David Stebbins were boyfriends when they took on the extremely complex roles in the world premiere of “Jerker,” Robert Chesley’s landmark play in which two men engage in a full-blown love affair, strictly over the telephone, with a final scene that played like Greek tragedy. By the end of the local run and a tour of several cities in America, both actors had full-blown AIDS and were full-fledged lovers. Their onstage lives had melded in a magically macabre way; this was queer theater in which off and onstage merged with breathtaking results.

David Stebbins, Joe Fraser

Stars of the 1986 world premiere of Robert Chesley’s “Jerker.”

photo: Tom Cunningham

Today our theater fare has normalized — re-workings of hit musicals, revivals, the occasional new “gay play” without the requisite nudity, something slightly saucy but far from dangerous — but the return to offstage/rehearsal room/backstage shenanigans may have made an ineluctable comeback after all those tear-soaked curtain calls on AIDS plays.

Certainly after the AIDS crisis aimed its scurrilous arrow into the hearts of gay men and we were once again castigated as pariahs — specifically targeting our sexuality — we had motivation to reclaim the part of our identity that had been trashed, maligned, punished. Perhaps in those ensuing years, some hanky-panky returned to the shadows of the gay theater arena, an oasis of safety (we assumed) — neither rightly nor wrongly but humanly.

Artistic Director Michael A. Shepperd fired over allegations of sexual misconduct.

I think we are in the midst of a learning moment in light of the Michael Shepperd controversy. And I think the entire issue deserves more thought and less facile condemnation. Whatever occurred in the “he said/he said” imbroglio is less important to me than being open to understanding that gay men (and, please forgive me, but this piece is primarily about gay men) have a different emotional/sexual/sensual vocabulary under certain circumstances, based on the longstanding threat of certain segments of society — members of Congress, members of QAnon, members of their church, members of the Republican Party, members of the police department, members of their family — to criminalize their behavior.

Only within the past fifty years have things evolved but we are still — in spite of all the magnificent strides in our favor — called demeaning names, beaten up on school playgrounds, kicked out of our homes, and in extreme cases, murdered for being queer in 2021.

Wouldn’t heavy-duty compassion and therapy-driven listening have been a better solution on the part of Celebration Theatre’s Board rather than predictable accusations and earnest lawyers and money squandered and reputations jeopardized? Especially for a theater company whose Vision is clearly stated: “To be a recognized leader of award winning content while becoming catalysts of change in the world around us.”

Comments

Gay Theater Veteran Looks at Sex on Celebration Theatre’s Boards — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>